Beyond Survival

Why Dr. Clinton Boyd, Jr. is fighting for solutions that Black men and fathers deserve

I wasn't expecting fatherhood to hit me before my son first arrived more than two years ago. Movies made me think that as I fumbled through that first diaper change or car seat installation, I'd be caught off guard by something small. A shared gaze, the first smile, my son holding a finger tightly would be the profound moment when I understood fatherhood.

The switch happened well before all of that though. My wife, Brittany, and I walked into the first sonogram uncertain of what to expect. Was there anything concerning? What would the tiny little fetus look like? Was it measuring big or small?

Then, we heard the heartbeat. Each of the 160 or so beats per minute were ethereal, reverberating through the room. The switch had flipped in my brain. With remarkable clarity, I remember thinking, "Well, there it is. My job is now to make sure that heart keeps beating."

It is an awesome responsibility, and one that is a helpful guiding force in those early months of chaos.

But I do not think my moment of clarity, the switch that flipped, is unique among fathers. There is a necessary shift in priorities and in perspective that is a unifying experience.

That was where I started the conversation with Dr. Clinton Boyd, Jr. He is a researcher at Chapin Hall and executive director of Fathers, Families, & Healthy Communities (FFHC). Recently, he co-authored the report Breaking the Chains: Reclaiming Wealth, Power, and Dignity for Black Men with a partner organization, Equity and Transformation (EAT).

The report centers the experiences of 172 Black men and fathers across Chicago's West and South sides, unpacking how economic exclusion happens and what must be done to change it.

Before getting into the report though, I wanted to talk to Clinton about his own fatherhood switch.

Conversation has been edited for length and clarity.

What was that shift was like for you when you became a father?

Becoming a father at 15 didn’t just change my life. It awakened my purpose. I was still a boy on Chicago’s West Side, struggling to find my way without a roadmap or a safety net. What I had was love and the will to show up. Holding my daughter, I felt both joy and fear, but I made a decision. I wouldn’t disappear. I would defy the narrative. The world expected me to fail. But fatherhood pushed me to fight harder. To grow. To lead. To build a life that honored her presence. That moment broke me open and reshaped who I would become.

Years later, becoming a father again at 30 brought a different kind of reckoning. I was more stable and more grounded, but still unprepared in ways I didn’t expect. I had to let go of the version of the future I had imagined. Still, I leaned in. I chose responsibility instead of retreat. Presence instead of pride.

Now, when I speak up for Black fathers, I do it with lived conviction. Because I have been that scared teen, and I have been the grown man facing new fears. I know what is possible when we stop running. When we are embraced instead of erased. Fatherhood didn’t just shape my story. It gave me the courage to help others write a different one.

When you think back to 15 year old, new father, Clinton, what do you look back on that person and see?

I see a kid full of youthful energy and deep curiosity, curious about the family I came from, the family I was starting, and the community that shaped me. Even back then, I was thinking about more than just my own situation. I was really paying attention to what was happening around me.

When I looked at my community, I saw brilliance. People who were smart, ambitious, creative, but the environment we were growing up in didn’t always make space for that brilliance to thrive. It felt like our God-given greatness was constantly being stifled.

I knew I couldn’t just think short-term. I needed to build something lasting, not just for my daughter, but for the other young fathers, the boys coming up behind me, the families trying to make it in a system that wasn’t built for us. I didn’t have the words for “structural inequality” or “systemic barriers” back then, but I felt them. I lived them. And I saw how they chipped away at Black boys and Black men every day.

That moment, becoming a young father, set something in motion for me. And now, 21 years later, I’m still on that path. Still doing the work. And having conversations like this that bring it all full circle.

2024 Ascend Fellow Clinton Boyd, Jr.

2024 Ascend Fellow Clinton Boyd, Jr.

What was that shift was like for you when you became a father?

Becoming a father at 15 didn’t just change my life. It awakened my purpose. I was still a boy on Chicago’s West Side, struggling to find my way without a roadmap or a safety net. What I had was love and the will to show up. Holding my daughter, I felt both joy and fear, but I made a decision. I wouldn’t disappear. I would defy the narrative. The world expected me to fail. But fatherhood pushed me to fight harder. To grow. To lead. To build a life that honored her presence. That moment broke me open and reshaped who I would become.

Years later, becoming a father again at 30 brought a different kind of reckoning. I was more stable and more grounded, but still unprepared in ways I didn’t expect. I had to let go of the version of the future I had imagined. Still, I leaned in. I chose responsibility instead of retreat. Presence instead of pride.

Now, when I speak up for Black fathers, I do it with lived conviction. Because I have been that scared teen, and I have been the grown man facing new fears. I know what is possible when we stop running. When we are embraced instead of erased. Fatherhood didn’t just shape my story. It gave me the courage to help others write a different one.

When you think back to 15 year old, new father, Clinton, what do you look back on that person and see?

I see a kid full of youthful energy and deep curiosity, curious about the family I came from, the family I was starting, and the community that shaped me. Even back then, I was thinking about more than just my own situation. I was really paying attention to what was happening around me.

When I looked at my community, I saw brilliance. People who were smart, ambitious, creative, but the environment we were growing up in didn’t always make space for that brilliance to thrive. It felt like our God-given greatness was constantly being stifled.

I knew I couldn’t just think short-term. I needed to build something lasting, not just for my daughter, but for the other young fathers, the boys coming up behind me, the families trying to make it in a system that wasn’t built for us. I didn’t have the words for “structural inequality” or “systemic barriers” back then, but I felt them. I lived them. And I saw how they chipped away at Black boys and Black men every day.

That moment, becoming a young father, set something in motion for me. And now, 21 years later, I’m still on that path. Still doing the work. And having conversations like this that bring it all full circle.

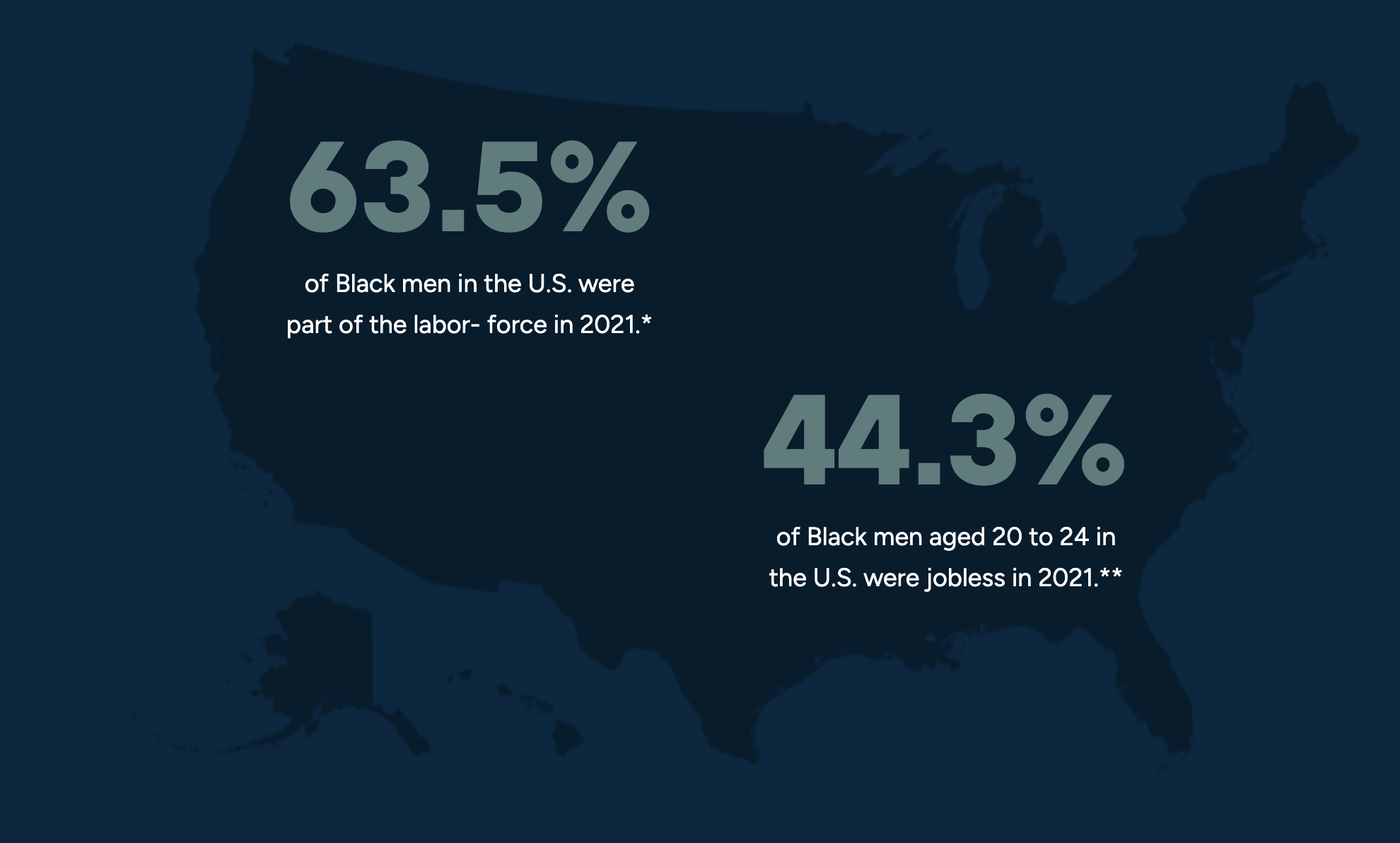

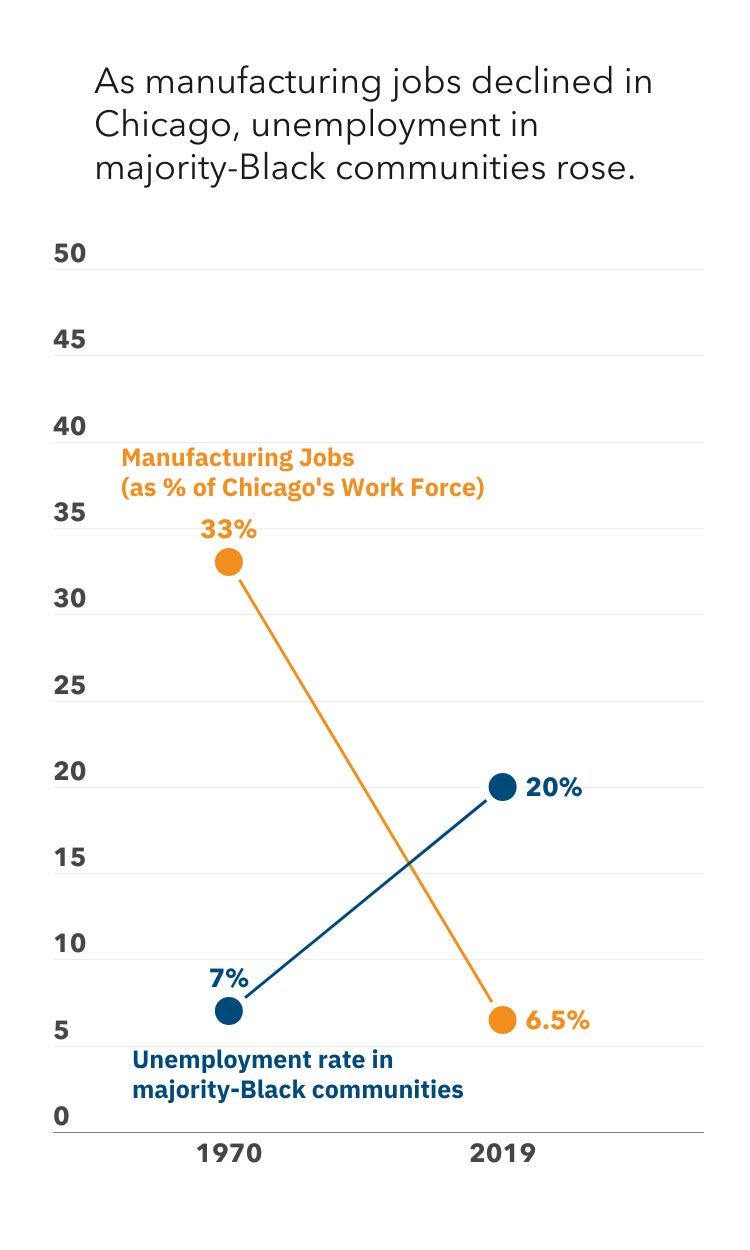

Source: Breaking the Chains

Source: Breaking the Chains

Before getting into the findings of your new report, Breaking the Chains: Reclaiming Wealth, Power, and Dignity for Black Men, one thing that I think distinguishes it from other kinds of reports, is that it's rooted in the history of what has what's come before this moment . Why was that historical grounding so important?

For me, it was essential. I come to this work not just as a sociologist, but as someone who’s always been drawn to the history of African and African American people. Even back when I was at Duke, the first class I taught was intro to African and African American history. That foundation has shaped the way I see the world and the way I approach my work. So, it just made sense that this report would start there too.

But more than that, history gives us clarity. Without it, it becomes easy to misrepresent what’s really going on, to tell stories that blame individuals instead of systems. We start believing myths instead of facing the truth. And in this country, we’ve gotten really good at ignoring the roots of the problem. We act like the struggles Black men face today are the result of bad choices or personal shortcomings, when in fact they’re the result of policies, structures, and systems that were intentionally designed to exclude us.

The economic isolation of Black men and fathers, our exclusion from wealth, our criminalization, our erasure, none of that is accidental. It’s historical. It’s systemic. So, we grounded this report in history to make that point undeniable. We needed people to understand that the disparities we’re naming aren’t about effort; they’re about design.

Black men didn’t build the barriers we face, but we’ve had to carry the consequences of them for generations. If we want real, lasting change, then we must start with the truth. And the truth is, this country owes Black men a debt, not just of resources, but of recognition, of restoration, and of repair. That’s the foundation we chose to build from.

So the backdrop of the report is the COVID 19 pandemic and how it affected Black men and fathers in Chicago. How did the pandemic and its aftermath affect impact Black men and fathers in Chicago?

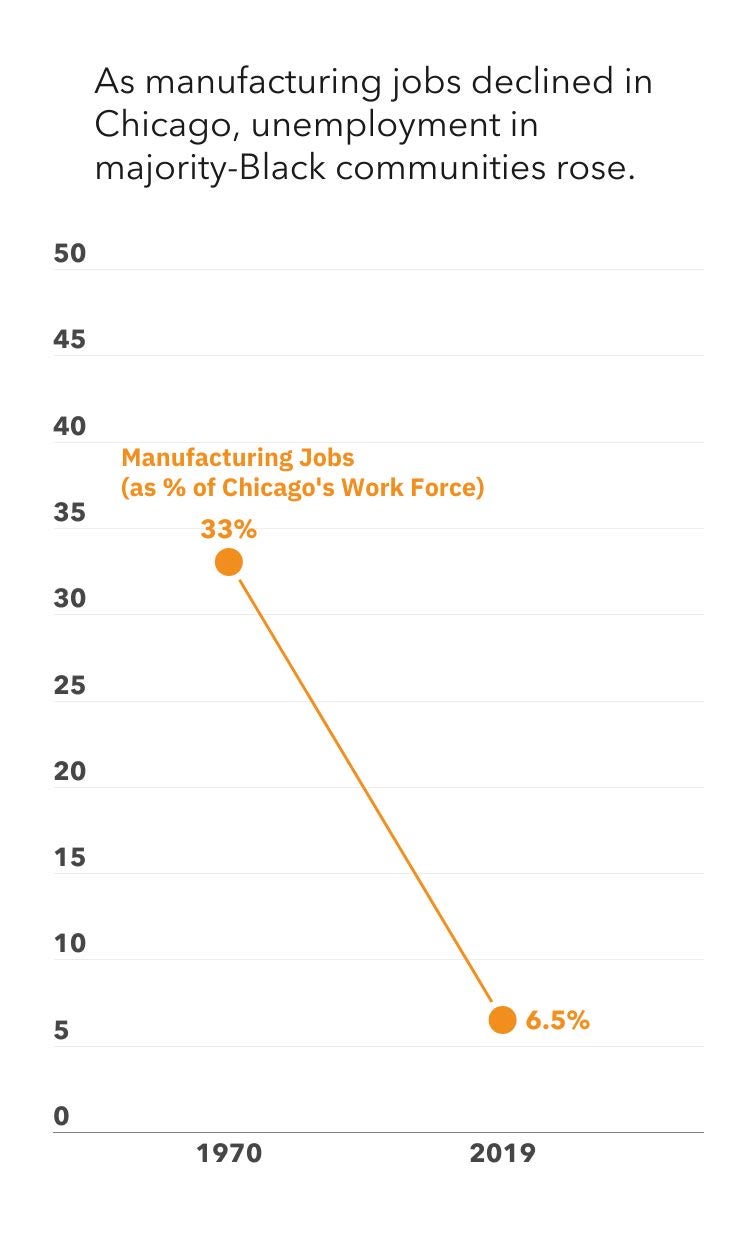

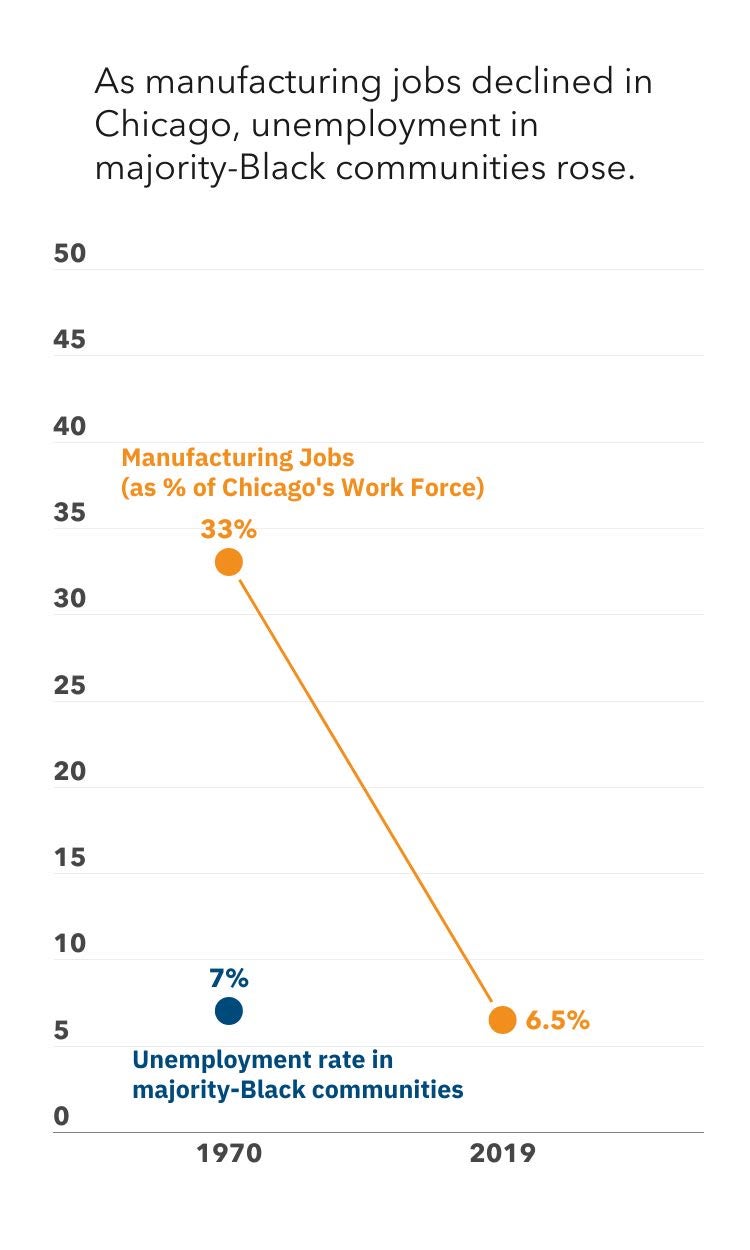

The pandemic didn’t cause the crisis for Black men. It revealed it. It exposed what had been true for a long time: that our systems are not built to support Black men and fathers, especially in a city like Chicago. For us, COVID wasn’t a disruption. It was a magnifier. It made it painfully clear just how disconnected Black men already were from the labor market, from economic opportunity, from basic stability.

While some communities were trying to figure out how to work from home, we were figuring out how to keep a roof over our heads and food on the table. And the truth is, even before the pandemic, many Black men in Chicago were locked out of quality jobs, pushed into low-wage, unstable work or shut out of the labor force entirely. The barriers weren’t new, but the consequences during COVID were sharper. And when the world told everyone to "bounce back," that didn’t reflect our reality. You can't bounce back to a place you’ve never had solid footing in.

We also can’t forget that our social safety net has never really included Black men. Whether it’s housing support, unemployment insurance, or even basic public assistance, these systems were designed in ways that either excluded us or criminalized us for needing help. And more than anything else, Black men rarely receive compassion, not in policy, not in practice, not in public perception.

That lack of support and recognition came through in the stories we heard. Men talked about the shame of not being able to provide, the pain of being separated from their kids during lockdown, and the emotional weight of feeling invisible in systems that claim to serve everyone. But they also talked about how they made a way out of no way, how they built side hustles, leaned on one another, and kept showing up for their children.

That’s the other side of this report. It’s not just about struggle. It’s also about strength. It’s about the resilience of Black men who, even when locked out, kept building and supporting each other. But let’s be clear: resilience shouldn’t be a job requirement. We shouldn't have to be superheroes just to survive.

We deserve more than survival. We deserve justice. We deserve dignity. We are at a point where we must demand both.

Before getting into the findings of your new report, Breaking the Chains: Reclaiming Wealth, Power, and Dignity for Black Men, one thing that I think distinguishes it from other kinds of reports, is that it's rooted in the history of what has what's come before this moment . Why was that historical grounding so important?

For me, it was essential. I come to this work not just as a sociologist, but as someone who’s always been drawn to the history of African and African American people. Even back when I was at Duke, the first class I taught was intro to African and African American history. That foundation has shaped the way I see the world and the way I approach my work. So, it just made sense that this report would start there too.

But more than that, history gives us clarity. Without it, it becomes easy to misrepresent what’s really going on, to tell stories that blame individuals instead of systems. We start believing myths instead of facing the truth. And in this country, we’ve gotten really good at ignoring the roots of the problem. We act like the struggles Black men face today are the result of bad choices or personal shortcomings, when in fact they’re the result of policies, structures, and systems that were intentionally designed to exclude us.

The economic isolation of Black men and fathers, our exclusion from wealth, our criminalization, our erasure, none of that is accidental. It’s historical. It’s systemic. So, we grounded this report in history to make that point undeniable. We needed people to understand that the disparities we’re naming aren’t about effort; they’re about design.

Black men didn’t build the barriers we face, but we’ve had to carry the consequences of them for generations. If we want real, lasting change, then we must start with the truth. And the truth is, this country owes Black men a debt, not just of resources, but of recognition, of restoration, and of repair. That’s the foundation we chose to build from.

So the backdrop of the report is the COVID 19 pandemic and how it affected Black men and fathers in Chicago. How did the pandemic and its aftermath affect impact Black men and fathers in Chicago?

The pandemic didn’t cause the crisis for Black men. It revealed it. It exposed what had been true for a long time: that our systems are not built to support Black men and fathers, especially in a city like Chicago. For us, COVID wasn’t a disruption. It was a magnifier. It made it painfully clear just how disconnected Black men already were from the labor market, from economic opportunity, from basic stability.

While some communities were trying to figure out how to work from home, we were figuring out how to keep a roof over our heads and food on the table. And the truth is, even before the pandemic, many Black men in Chicago were locked out of quality jobs, pushed into low-wage, unstable work or shut out of the labor force entirely. The barriers weren’t new, but the consequences during COVID were sharper. And when the world told everyone to "bounce back," that didn’t reflect our reality. You can't bounce back to a place you’ve never had solid footing in.

We also can’t forget that our social safety net has never really included Black men. Whether it’s housing support, unemployment insurance, or even basic public assistance, these systems were designed in ways that either excluded us or criminalized us for needing help. And more than anything else, Black men rarely receive compassion, not in policy, not in practice, not in public perception.

That lack of support and recognition came through in the stories we heard. Men talked about the shame of not being able to provide, the pain of being separated from their kids during lockdown, and the emotional weight of feeling invisible in systems that claim to serve everyone. But they also talked about how they made a way out of no way, how they built side hustles, leaned on one another, and kept showing up for their children.

That’s the other side of this report. It’s not just about struggle. It’s also about strength. It’s about the resilience of Black men who, even when locked out, kept building and supporting each other. But let’s be clear: resilience shouldn’t be a job requirement. We shouldn't have to be superheroes just to survive.

We deserve more than survival. We deserve justice. We deserve dignity. We are at a point where we must demand both.

"We deserve more than survival. We deserve justice. We deserve dignity. We are at a point where we must demand both.”

- Dr. Clinton Boyd, Jr.

That was actually one of the most illuminating things in the report, how honestly the fathers and Black men talked about their own vulnerability, which I think is a testament to that resiliency that you're talking about. How did you, as researchers, set the conditions that allowed for Black men and fathers to be vulnerable and provide you with those responses?

It really came down to our approach and how we engaged the men from the very beginning. We held focus groups with about 172 Black men and fathers across Chicago, in partnership with Equity and Transformation. But what made the difference was that many of these men were already connected to our programs. There was a foundation of trust. They didn’t just see us as researchers. They also saw us as part of an opportunity structure they could rely on, even before we asked a single question about jobs or family life.

We were also really intentional about who facilitated those conversations. Our focus group facilitators were Black men from the same communities, men with lived experience who could relate to what participants were going through. That matters. People open up when they feel seen, not studied. And we made sure our facilitators were trained in restorative justice practices, because we knew the conversations could unearth a lot of pain.

When you're talking about Black men and the inability to work, or the struggle to provide, it cuts deep. It touches on identity, self-worth, and the weight of expectation. So, we created space for those feelings. We made it clear that their stories would be handled with care, and that they weren’t just venting into the void. We let them know: What you’re sharing with us is going to shape real solutions. This isn’t just research. It’s restoration work.

And I think that’s why they were willing to be so raw and real with us. Because we met them with respect, with empathy, and with a commitment to do something meaningful with what they gave us.

You provide so many strong examples of what systemic injustice looks like in practicality. And one of the ones that I've been interested in since working with Ascend but, is the issue of the burden of child support debt, particularly for men impacted by mass incarceration. I'm wondering if you could explain why child support debt is so emblematic of these systemic issues.

That’s a really important question, and honestly, one that doesn’t get nearly enough attention. Child support debt is a prime example of how systems that are supposed to support families end up doing real harm, especially to Black fathers. And while child support debt can impact all fathers, there’s a disproportionate burden placed on Black men, particularly those who’ve been impacted by incarceration.

What often happens is that child support orders are set based on outdated or inflated income estimates. They don’t reflect a father’s actual financial situation, especially if he’s working low-wage or unstable jobs. So, from the very beginning, the amount he’s ordered to pay may already be unrealistic. Then, if he ends up incarcerated, that order doesn’t automatically adjust. Unless there’s a formal modification, which can be hard to access, that debt just keeps building while he’s behind bars and unable to earn any income.

Even though some legislative reforms have been introduced in recent years to make child support more responsive to the realities of incarceration, we still have far too many men stuck under the weight of old orders and back-owed debt. And the consequences are devastating. Any money they manage to earn, especially from formal employment, gets heavily garnished. That makes it even harder to stabilize their own lives, much less support their children in meaningful ways.

But beyond the financial strain, there’s an emotional and psychological toll. Men have told us about the shame, the frustration, the deep sense of failure. It leaves many of them feeling disposable, unseen, as if their only worth is tied to a dollar amount.

And that’s one of the most painful truths: the system reduces fatherhood to a financial transaction. It overlooks all the other ways that dads contribute, emotionally, spiritually, through time and presence. It sends the message that if you can’t pay, you don’t matter. And in that way, it criminalizes poverty. It punishes men not for being unwilling, but for being unable to meet an unrealistic financial demand.

If we’re serious about strengthening families, we must stop using child support as a tool of punishment. We need to reimagine the system so that it sees Black fathers as full partners in parenting, not just as paychecks. That means recognizing their value beyond money, supporting their efforts to be present in their children’s lives, and creating policies rooted in dignity, equity, and care. When we do that, we don’t just help fathers. We help entire families and communities thrive.

When I saw reparations as a policy recommendation in your report, I started thinking back to some of Dr. Sandy Darity's work at Duke, which I know you're familiar with.

And one of the through lines in that work is the importance of having the political will necessary to move policy solutions forward. You can have really well designed policies, but if you don't have the will to enact policies, it’s hard to make change. So realizing that the report hasn't been out all that long yet, but what have you noticed any findings or recommendations that seem to be resonating with people in a way that might start to grow the political will?

One area that’s definitely gaining traction is the recommendation around guaranteed income. The organization we partnered with, Equity and Transformation (EAT), has already been doing powerful work in this space. They've led efforts to create targeted guaranteed income pilots for system-impacted folks here in Chicago, primarily Black men.

At FFHC, we’re building on that momentum. Right now, we’re laying the groundwork for a targeted guaranteed income program specifically for Black fathers. We’re studying what’s been done, learning from organizations that have implemented similar efforts, and engaging with the philanthropic sector to explore what long-term investment could look like. And because we’re based in Chicago, we’re fortunate to be in a city that’s already piloted guaranteed income at the municipal level. So locally, there’s definitely an appetite for deeper conversations about what a targeted guaranteed income model could mean for justice-impacted Black men and fathers.

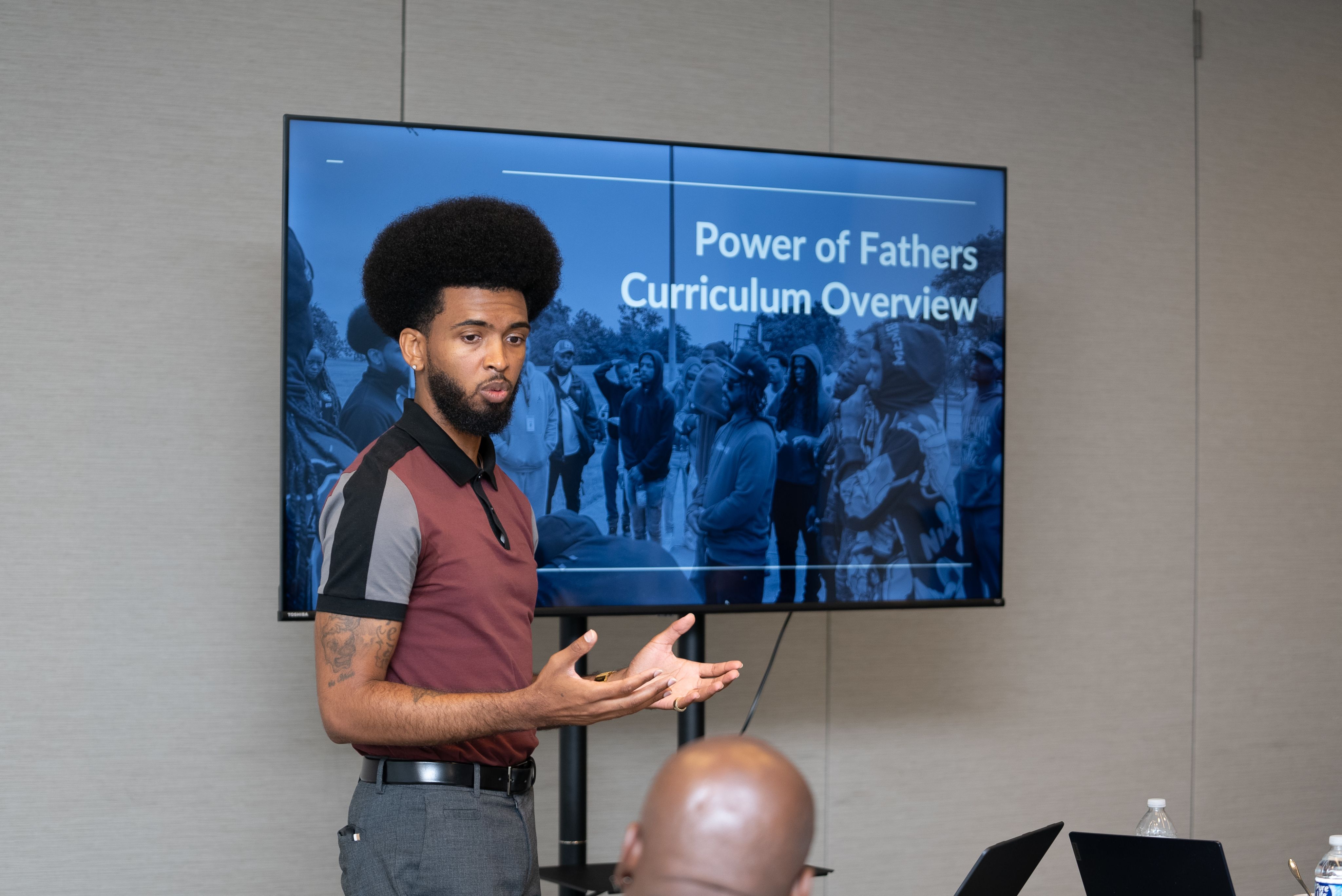

The second area where I’m seeing movement is around investing in fatherhood programming. Now, I’ll be honest, I’m not always a fan of how people enter the conversation. Too often, it starts from a deficit-based perspective, framing Black fathers as problems to be fixed. But for us, the approach is entirely different. We see these men as assets, to their children, to their families, and to their communities.

And it’s not just about funding fatherhood programs. The type of programming matters just as much as the investment. We need trauma-informed, culturally grounded, and strengths-based approaches that see Black fathers not as broken, but as burdened. When you invest in our healing, our leadership, and our wholeness, that’s when you start to stabilize families, strengthen communities, and interrupt cycles of harm that have been engineered over generations.

For me, the recommendations in the report weren’t about making a political pitch. They were about telling the truth. We laid out what needs to happen because it’s right. It’s just. It’s necessary. Whether policymakers or institutions choose to act on that is their decision, but our responsibility is to make it plain. To name what justice looks like for Black men and fathers. This report isn’t about asking nicely. It’s about offering a clear roadmap toward dignity, equity, and repair. What folks do with that truth will reveal where their values really stand.

“We laid out what needs to happen because it’s right. It’s just. It’s necessary. Whether policymakers or institutions choose to act on that is their decision, but our responsibility is to make it plain.”

- Dr. Clinton Boyd, Jr.

“We laid out what needs to happen because it’s right. It’s just. It’s necessary. Whether policymakers or institutions choose to act on that is their decision, but our responsibility is to make it plain.”

- Dr. Clinton Boyd, Jr.

If you had a magic wand to enact one policy solution what would it be?

Without question, I’d use it to implement a comprehensive reparations program. That’s the policy solution that sits at the root of so much of what we’re dealing with today. The racial wealth gap in this country didn’t just happen, it was built, brick by brick, through generations of government-sanctioned harm. Slavery, Jim Crow, redlining, mass incarceration, these were all policies, not accidents.

So, if policy created the gap, then policy must close it. And the federal government, the same one that upheld those systems of oppression, is both responsible and fully capable of doing that work.

Reparations, to me, isn’t about handouts. It’s about repair. It’s about recognizing the debt that’s owed and making real investments in Black communities to restore what’s been systematically taken. And no, it’s not just about money. It’s about land, housing, education, and economic opportunity. It’s about giving Black people not just a way out, but a way forward.

At the end of the day, this isn’t about charity. It’s about divine justice. Reparations is how we begin to right the wrongs and, assuming no new atrocities occur, finally create the conditions for Black men, fathers, families, and communities to truly thrive.